- Home

- Gregory Blake Smith

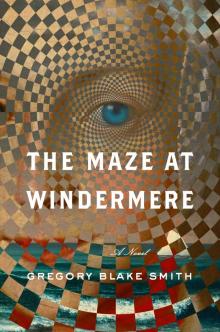

The Maze at Windermere Page 3

The Maze at Windermere Read online

Page 3

Though the sort of locks they seemed to mean in their snide, vulgar, insinuating, insulting way were most certainly not the sort he opened.

It was not lost on Mr. Franklin Drexel that his days as a lapdog were numbered. He was thirty-three. The mange was beginning to show itself in the form of little gray hairs which this past winter he had begun to color with a light tan shoe polish but which would eventually be too numerous to disguise. He knew who he was. He was the boyish, handsome type. He wasn’t the distinguished, gray-templed type. Nor was he likely to effect the transmogrification from the one to the other with any grace. It would be a slow slide, he knew, but sometime before he was forty he would have ceased to appear in TOWN TOPICS or any of the other scandal sheets. His invitations would slip from Mrs. Belmont to Mrs. James to Mrs. Beaulieu and then to the fringe knocking on the doors of the great Newport cottages, and then to those who weren’t even coming up the walk and who, for a time, would consider him a catch—Mr. Franklin Drexel and his stories of drinking lime rickeys with Alva Belmont and Irene Auld at a Casino outing—but then those invitations too would cease to make their way down to Fourth Street. He was not a fool. And he kept his eyes open. And this he knew: the social blasphemy that was charmingly risqué in an impish jeune homme would prove coarse and repugnant in a man of middle age. The impish jeune homme must take care to land feet first on Fifth Avenue before he became an out-at-the-collar vieillard.

“I am not quite sure, my dear Franklin, what you mean when you say you would not need to water a desiccated widow. Would she not need watering more than a young girl?”

But he had a few years yet in which to turn around. His tailor had yet to increase the measure of his waist. No one knew of the shoe polish. He had time to appraise just what the best carte de visite might be, the entrée that would not be subject to revocation by the whims of bored women or a slight distension of the jowls. But there should be no mistaking that such an entrée needed to be secured. He had neither money nor name—or at least not enough of either. He had rather his looks and his wit and the studied luck of having charmed the right women at the right moment, but all that would evaporate with time and familiarity. If the thing needed to be done, he sadly realized, now was the time to do it. Now when he was the Register’s lapdog—petted and fondled and fed.

“If called upon to water a wife,” he responded with a dignified elevation of his chin, “I will of course do so. I am a man of duty, as you both know. Indeed the name of Drexel is acknowledged as a synonym for Duty all along the Atlantic Seaboard. I insist you stop laughing. Point me in the direction of a lonesome Lily and I will show you—I will souse her with spray! She will beg you to rescue her!—though really I must repeat that I should much prefer, for my boutonnière, a dried Daisy.”

And then there were the men—the husbands. They had yet to concern themselves with him. He was their wives’ plaything—an embellishment of Newport and not of New York—and it was the wives who ruled Newport. But should he rise in their field of vision so that they inquired about him, they would—at the very least!—come to know him as a remittance man. And it was only one step from being found out as a man who was kept by his family with a monthly check to being seen as a cad or bounder or worse. He could not afford to have the men communicate a view of him as a fortune hunter to the women. His campaign of deft parries, his witty deflection of the topic of marriage, his careful sculpting of the Free Young Man Unwilling to Submit to the Connubial Yoke would be lost on the men. They would cut through that particular Gordian knot with one swift slice. He knew men. Indeed, he knew men and women. It was one of the compensations for being who he was.

“Or perhaps, after all,” he mused, “I should prefer a Dollar Princess. That is, if I could elbow aside the English Barons and the Italian Counts.”

And as soon as he’d said it, he knew he had gone too far. Mrs. Belmont let her eyes rest fully on him. She had herself famously succeeded in marrying her daughter Consuelo to the Duke of Marlborough the previous November. It was a subject that could only be spoken of as a testament to her power and her status. Not to her wealth. Any suggestion of the Duchess of Marlborough as a Dollar Princess—and she was, after all, the Dollar Princess ne plus ultra—was beyond the pale. But as he had so often done before when he had gone too far, he found the best route out was to go even further.

“Or have you used up all the Dollar Princesses?” he asked. And when Mrs. Belmont continued to fix him with her gaze: “Surely you have one in your pocket or hiding under the bed. I should like a wife who had the good sense to hide under the bed. Indeed, I should set her up with reading material and a pot of tea. Oh, now what are they doing?” he cried, turning back to the court below as the spectators burst into applause and one of the young men leapt the net. He made an exasperated face and threw his palms in the air as if the world were just too much—didn’t they agree?—and then rose and held his white linen arm out for Mrs. Belmont to take, and the dear monster, with a sigh at the utter impossibility of the dear young man, took it. And then he held his other arm out for Mrs. Auld and the three of them made their way along the curving piazza down the steps onto the grass where under its parasols and straw boaters the beau monde milled and observed itself.

He had a welcoming word for everyone, and a ready smile, and when the time was right he left the two women to fetch them each an ice. He allowed himself a bit of loitering—breathing a little easier now and keeping an eye on the men retiring into the Casino. He greeted those he knew, smiled at the young girls who smiled back at him, watched the hubbub surrounding the tennis players.

After a quarter hour, laden with ices, he rejoined the women only to find they had, in his absence, conjured a desiccated widow.

“You know Ellen Newcombe, I think?” said Mrs. Belmont, and indeed he did. He had made Mrs. Newcombe’s acquaintance this past winter, he believed. He smiled and offered her his ice, made it seem as though he had known she would be there and had brought the extra ice just for her.

She was dressed smartly in a bicycling costume, a lavender affair with an almost masculine shirtwaist, leg-o’-mutton sleeves, and blousy Turkish bloomers that gathered high on the shin. She was thin and though the line of her was, he supposed, not unpleasant to look at, she had, he thought, an unfortunate face. It was a face that somehow managed to look permanently in pain and at the same time hopeful of release—rather, he thought, like a mistreated dog. He supposed the pain had something to do with the loss of her husband three years earlier. He supposed, too, that he was not the most generous arbiter of woman’s faces. But if nothing else, it was a face that had yet to realize it was too old for the bicycling dress.

“You will not tell us, my dear Mrs. Newcombe, that you rode that preposterous machine of yours all the way in from Windermere?”

She certainly would tell them. She found bicycle riding marvelously invigorating. Were it not for her young children, she would utterly dispense with her carriage. Did not Mr. Drexel share her love of bicycle riding?

Mr. Drexel did not, but said he did. Children? he thought.

They talked of the things they were wont to talk about, of the highlights of the coming season, of the Hobbyhorse Quadrille of the past winter which had not yet lost its piquancy, and of course of Mrs. Belmont’s renovations at Belcourt. She was inundated with architect’s elevations, she said, with marble and drapery samples. Mrs. Auld didn’t know how her friend kept her head above things, but she was a whirlwind of energy, they all knew. Indeed, the whirlwind had in ten months managed to divorce her husband, to weather the scandal that that divorce had caused, to get her daughter married to the Ninth Duke of Marlborough, and then herself married to the renowned horseman Mr. Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont (whose father had been a Jewish banker, but never mind that). She was now mistress of two of the most famously lavish cottages in Newport, her own Marble House, which had been a birthday present from her first husband, and her new husband�

�s sixty-room Belcourt. The latter somewhat infamously had stables for its ground floor. Franklin had not seen them himself, but he could imagine they were no ordinary stables.

“Alva, I think you are only happy when you are up to your elbows in mortar,” said Mrs. Auld.

“I like to build things,” Mrs. Belmont said with a firmness to her round face—it always put Franklin in mind of a pugilist’s. “I like to make things happen.” And she looked at Franklin as if to gauge his understanding.

“If I had a calling,” he remarked, “a calling to miss, I mean, it would be that of an architect. Don’t you think I would make a fine architect, Mrs. Newcombe?”

“You, my dear,” Mrs. Auld interrupted, “were made to inhabit beautiful homes, not to build them.”

“Ah!” he said with a sad inward smile as if this—alas!—were indeed his fate.

Some others came over and the conversation turned general. From time to time Franklin thought he could feel the woman’s eyes on him, the woman for whom he would have to forge his charm into a trap if he wanted her Sixty-second Street mansion, and her bank account, and—delightful development!—this Windermere she spoke of. He tried to hold himself as he thought a potential husband ought to look. Clean line about the jaw, shoulders square, serpent’s tail well hidden. His ankles were beginning to sweat with the effort when he heard his name called over the tops of heads.

“I say, Drexel! Come have a smoke!”

He smiled an excuse to Mrs. Auld, to Mrs. Belmont, to Mrs. Newcombe. “The fairer sex calls,” he said with a polite bow, and then with just a tint of intimacy: “Charmed to see you again, Mrs. Newcombe.”

“Don’t forget tea,” Mrs. Belmont reminded him. She gave him her own meaningful look. “You’re coming of course.”

“Madam,” he said as he backed away.

“At the old house! At Marble House!”

A tactical stroke, he thought as he turned and started across the smooth grass toward the Casino, not to appear too eager to drape his dressing gown over Mrs. Newcombe’s newel post.

Summer 1863

~For my twentieth birthday Father presented me with this lovely bound notebook. He has written on the inside leaf in his formidable script “From Henry James, Sr. to Henry James, Jr. May you make upon these pages an impression of the person.”

I will try, though I think the person whose impression these pages show may not be to Father’s liking.

For I have taken to “hanging about” the hotels this summer watching the leisure population. As there is a sharp divide between the Newport summer people and those who live year-round, there is no need to worry that someone of Mother’s or Father’s acquaintance will observe me. In that sense I am a spy, loitering about the hotel piazzas, just another idling young man who has managed to avoid this terrible war, one whose head is perhaps slightly too large and whose stature is slightly too small (and there’s the unfortunate stammer which he does his best to hide), but with a touch of elegance, standing around and observing the world.

And what I see I jot down in this notebook (I shall be taken for a journalist!), ideas for characters, situations, complexities, the melting look of Miss So-and-So as she gazes out from under the brim of her bonnet.

Here’s a budding novelist’s question: Can the appearance of people suggest their reality? Do we “read” the psychological in the tilt of a lady’s fan, in a pair of spectacles askew upon the bridge of the nose? And could one let those appearances, the dress, conversation, postures of the Newport beau monde, suggest their inner lives, and so make of them subjects that one might “work up” in sketches or stories? If I am really to embrace the writer’s life, might not such a Notebook serve as a fount into which one might dip one’s pen time and again?

I must work up the nerve to inform Father that I shall not be returning to Cambridge in the fall. I can no longer pretend to be studying the Law. Odious enterprise!

~I have seen the young lady several times now and feel I must note her here. (Why one person gives us an impression and another does not is a mystery, but so it is.) What is perhaps most striking about her is her height. For she is very tall, taller than most men I suppose, certainly taller than poor Harry James! And she is thin, without the usual local places of volume I believe it is considered desirable for young women to possess. She has a sleekness and a bearing most striking. And since the first time I saw her was on the archery field at the Atlantic, she had I thought a look rather of the goddess Diana, a regal chastity that was suggestive. She was a novice at the sport, yet she was able to draw back the bowstring and let loose her arrow with considerable determination.

This is the subject I have spun about her. The business of Newport, it is said, is flirtation. And I have heard it suggested (it is a conversational shuttlecock among Newport residents) that there are young women of the working middle classes who save year-round in order to stay at one of the finer hotels that they might be “thrown in” with a better class of people. The hope then is that she will bewitch some man whose wealth, while not of the first rank of course, would be beyond what she might expect had she stayed home in Hartford or Trenton. We have here a game of presentation and withholding, of infatuation and discovery, a social campaign just on the perimeter of malfeasance.

So what is the necessary matériel for such a campaign?

First of all, the young woman must be beautiful. For that is what she is “selling.” Secondly, she must be able to dress well enough so that her antecedents, for a three- or four-week period at any rate, are hidden. (This is no mean challenge, for the denizens of the hotels are forever changing: morning clothes, riding habits, clothes for tennis and croquet, and of course gowns to be worn for supper followed by dancing or a concert.) Thirdly, she must be able to converse intelligently, and to have enough sense to smile charmingly when the conversation turns to matters beyond her, and her accent, if she has one, must be part of her charm, and not reveal her father as a shopkeeper. But most of all (it bears repeating) she must have a physical splendor that would make a widower (who ought to know better), or a young second son (who oughtn’t), care only about having her, and quickly.

The whole enterprise is predicated upon the glow of her beauty prompting a proposal which, later on, when the antecedents are known, there will be no withdrawing.

And those are the brushstrokes I painted her with, observing her, first in the ladies’ archery, where her posture was superb and her sleek flanks on display; and then the next afternoon on the veranda, listening to her converse with a woman who appeared to be her mother (I shall make her an aunt), the spy sitting at a little wicker table pretending to read the Revue des Deux Mondes, she standing at the railing overlooking the gardens.

Perhaps I might make her a dressmaker as a way of accounting for her fashionable clothes, and ground the conceit by having her take apart imported French gowns so that she can use the pieces for patterns (revealing detail!). However it is managed, the writing must be charged throughout with the atmosphere of the Newport summer, with the unreality of society at the hotels, the meringue of artificial talk against the ruddy glow of hidden motives, and for the girl and her accomplice-aunt, the awareness that the clock is ticking.

~Today she was in the company of a rather vulgar young boy I take to be her brother and whose name, if I heard aright, is Harry. Odd coincidence.

Question: to have names which signify (as Mr. Hawthorne does), or to allow them to be “merely” real as in life?

The thing is to see them, to see one’s characters in all their complexity, all their blind groping, engaged as they must be in the hubbub of connection and courtship and “getting on” where clarity lies remote, and to represent them without stint, yet without embellishment, to have them feel the beat of their hearts though they may not know for what their hearts beat. The feeling must be all theirs, the clarity all mine!

Ruskin says that the greatest

thing an artist can do is to see something and to tell what he sees simply and honestly, and that to do so is poetry, prophecy, and religion, all in one.

As to the subject of the designing dressmaker: I must endeavor to understand (that is to say, to imagine) the condition of her heart as well as the magnitude of her ambition. It will not be enough to present her merely as a “climber.” The reader must be made to understand the forces that impel her, the mother’s resentment, the father’s discontent, the jealousy she feels for the Washington Square women she attends in the shop, their slighting treatment of her, the beauty she catches glimpses of when she travels to the wealthy homes to fix a hem or take in a bodice, and which she dreams of having about her always.

~Now, after some several days of spying (I shall be taken for a pickpocket!), here is my sense of the Newport hotels and their clientele, along with some details that may prove useful, for my story’s setting must have the perfume of the real world.

My Diana and her mother are staying at the Ocean House on Bellevue Avenue (the extension of what used to be called Jews Street), which is the most massive of all the new hotels with its four stories and three hundred rooms and its full-length verandas at both the first and third stories festooned with gothic tracery. The Ocean is accounted as catering to the best clientele (one day I saw delivered in wagons about thirty trunks, one of which, I heard one of the draymen exclaim in his Irish burr, was the size of a Dingle shanty). They sound a Chinese gong for supper, and afterwards the musicians of the Germania Society play while the guests promenade in their fashionable dress. They have a large saloon for concerts, and a wide central hall 250 feet long where balls are held and from which the servants take their name of “hall boys.” Perhaps too elegant (and expensive) for my dressmaker.

The Atlantic House, of the style called Greek Revival (though of wood and white paint so bright it blinds you in the sunlight), is said to have rivaled the Ocean for elegance and the fashion of its clientele, but since the bombardment of Fort Sumter and the loss of Annapolis it is taken over by the Naval Academy.

The Maze at Windermere

The Maze at Windermere